In Western musical notation, the length and relative timing of notes are shown on a staff, where the vertical position of a note (in notation) on the staff represents which note (on the scale) is to be sung or played. The mentality of Byzantine psalmody notation is vastly different. In Byzantine psalmody notation, there is no staff, only a single row of markings. Each note (in notation) shows which note (on the scale) is to be sung relative to the note that was just sung. Byzantine psalmody notation thus shows the intervals between notes, rather than which note (on the scale) each note (in notation) represents. In addition, there are markings in Byzantine psalmody notation for representing the length of notes and other characteristics (such as tying notes together, changing the force of a sung note, increasing volume, etc.)

In Byzantine psalmody, the notes in notation which represent these intervals are called neumes. There are ten basic neumes for the most common intervals which are then combined to create larger intervals. These neumes form the basis of the Byzantine psalmody notation. Below are neutral neueme and the four always ascending neumes.

1. Ison

The ison is a unique neume. While all the other basic neumes indicate either ascent or descent in notes, the ison indicates a repetition of the same note. For instance, if the note before an ison was Πα, the note sung on the ison is also Πα.

2. Oligon

The oligon is the basic neume of ascent. It indicates an ascent of one note from the note previously sung. For instance, if the note before an oligon was Πα, the note sung on the oligon is Βου.

3. Kentimata

The kentimata is another neume of ascent. Like the oligon, it indicates an ascent of one note from the note previously sung: the kentimata is used, though, when the same syllable is repeated as the previous note. For instance, if "O" is sung on Πα and the next note is the same "O" being sung on Βου, then a kentimata is used; if the next note is a "Lo" sung on Βου, though, an oligon would be used.

4. Petaste

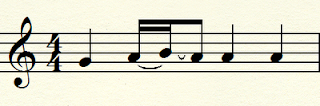

The petaste is another neume of ascent, and it also represents an ascent of one note. The uniqueness of the petaste is not when it is used, as the kentimata is separated from the oligon, but in how it is sung: the pesaste involves a quiver of the voice, "a rise of the sound, a little higher from the natural pitch of the tone at hand" (GMT I.II.IV.139). In other words, there is a quick rising of the voice to the next note higher and then back down. The following example depicts this, first in Byzantine psalmody notation, then in Western notation (only matching intervals, not the notes themselves).

5. Hypsile

The hypsile is an interesting neume of ascent. While it is counted among the basic neumes, it never appears on its own: it only appears in combination neumes, where it indicates an ascent of either four or five notes. It will be explained in greater detail when discussing combined neumes, where it is actually used.

To finish this post, here is an example of ascending the scale using these neumes (without the hypsile, of course), in both Byzantine psalmody notation and Western notation.

In Byzantine psalmody, the notes in notation which represent these intervals are called neumes. There are ten basic neumes for the most common intervals which are then combined to create larger intervals. These neumes form the basis of the Byzantine psalmody notation. Below are neutral neueme and the four always ascending neumes.

1. Ison

The ison is a unique neume. While all the other basic neumes indicate either ascent or descent in notes, the ison indicates a repetition of the same note. For instance, if the note before an ison was Πα, the note sung on the ison is also Πα.

2. Oligon

The oligon is the basic neume of ascent. It indicates an ascent of one note from the note previously sung. For instance, if the note before an oligon was Πα, the note sung on the oligon is Βου.

3. Kentimata

The kentimata is another neume of ascent. Like the oligon, it indicates an ascent of one note from the note previously sung: the kentimata is used, though, when the same syllable is repeated as the previous note. For instance, if "O" is sung on Πα and the next note is the same "O" being sung on Βου, then a kentimata is used; if the next note is a "Lo" sung on Βου, though, an oligon would be used.

4. Petaste

The petaste is another neume of ascent, and it also represents an ascent of one note. The uniqueness of the petaste is not when it is used, as the kentimata is separated from the oligon, but in how it is sung: the pesaste involves a quiver of the voice, "a rise of the sound, a little higher from the natural pitch of the tone at hand" (GMT I.II.IV.139). In other words, there is a quick rising of the voice to the next note higher and then back down. The following example depicts this, first in Byzantine psalmody notation, then in Western notation (only matching intervals, not the notes themselves).

5. Hypsile

The hypsile is an interesting neume of ascent. While it is counted among the basic neumes, it never appears on its own: it only appears in combination neumes, where it indicates an ascent of either four or five notes. It will be explained in greater detail when discussing combined neumes, where it is actually used.

To finish this post, here is an example of ascending the scale using these neumes (without the hypsile, of course), in both Byzantine psalmody notation and Western notation.

St. Ephraim the Syrian, pray for us!