St. John of Damascus (676-749), also known as St. John Damascene or Chrysorrhoas ("streaming with gold"), served as Chief Councilor (

Protosymbullus) of Damascus under Muslim rule before later retiring to live the monastic life in the Monastery of St. Sabbas near Jerusalem. He was a prolific writer whose work was incredibly influential, even to this day. A particularly important note about his work was his exposition of the theology underlying icons: his work was thus key to the Seventh Ecumenical Council, Nicea II (787). The Eastern Church often refers to him as "the last of the Fathers," and he is a Doctor of the Church often referred to as the Doctor of the Assumption. His feast day in both the Western and Eastern Churches is December 4, though from 1890-1969 it was celebrated on March 27 in the Western Church.

St. John was brought up under Muslim rule in Damascus, where his strong Christian family held high hereditary public office under the caliphs. When he reached the age of 23, his father found a Sicilian monk named Cosmas among prisoners of war, and this monk became the Christian tutor of St. John and his foster-brother, St. Cosmas the Hymnographer. St. John eventually gained a post as

protosymbullus of Damascus due to the high political status of his father.

In 726, the Byzantine emperor at the time, Emperor Leo the Isaurian, released an iconoclastic edict, which made St. John furious. The saint at that time wrote his first work,

Three Apologies Against Those Who Attack the Divine Images. The iconoclastic emperor was not pleased, so, upon finding a manuscript written by St. John, Leo forged a letter in which St. John was supposedly offering to betray the city of Damascus into the Emperor's hands. The caliph who ruled Damascus did not accept St. John's pleas of innocence, and he punished the saint by cutting off his right hand.

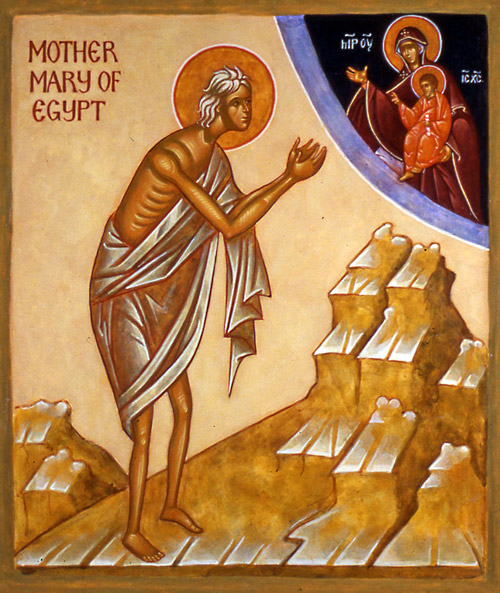

To the utter shock of the caliph, St. John's hand did not stay detached: after praying before an icon of the Virgin Mary, the saint's hand was miraculously reattached. In order to thank the Theotokos for this miracle worked through her intercession, St. John created a silver cast of his hand and attached it to the icon, thus giving the icon the name

Trojeručica, or the Three-Handed Theotokos.

St. John of Damascus entreating the icon of the Theotokos for healing

Following this miracle, the caliph apologized for his false accusations, and he offered St. John his same public office. The saint declined, though, instead retiring to the Monastery of St. Sabbas near Jerusalem, where he spent the rest of his life in fervent prayer and copious writing until his death in 749. Shortly after his death, he was revered as a saint, and in 1883 the Holy See named him a Doctor of the Church, placing him on the universal Church calendar in 1890.

As mentioned above, St. John was a copious writer. His first work,

Three Apologies Against Those Who Attack the Divine Images, is most likely the most important work on the theology of icons, and it was highly influential for the Second Council of Nicea. A discussion of some of his arguments, along with those of St. Theodore the Studite, can be found in

an earlier post of mine. Below is a fantastic quote on our "salvation through matter" from the first

Apology:

"I do not worship matter; I worship the Creator of matter Who became matter for my sake, Who willed to take His abode in matter; Who worked out my salvation through matter. Never will I cease honoring the matter which wrought my salvation! I honor it, but not as God...God's Body is God because It is joined to His Person by a union which shall never pass away" (1.16).

Another major work of St. John's was

The Fountain of Wisdom (

Fountain of Knowledge), a work divided into three parts:

Philosophical Chapters,

Concerning Heresy (which includes one of the first Christian polemic writings against Islam, and the first from a member of the Byzantine Church), and

An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith (

De fide orthodoxa) (the first work of Scholasticism in the Eastern Church). The last section of this work, a summary of the dogmatic writings of the Fathers, is quoted and referenced frequently by St. Thomas Aquinas in his

Summa Theologica.

Besides those two greatest works of his, St. John wrote many shorter works, including

An Introduction to Elementary Dogmatics,

On the Two Wills of Christ (written against the Monothelites), and, a work with a fascinating title,

On Dragons and Ghosts. St. John also penned the

Octoechos (

Οκτοηχος), the liturgical book containing the weekly variable texts in the eight tones of Byzantine Psalmody. (St. John is considered to be the one who systematized the eight-tone system of Byzantine liturgical music.) Among multiple canons that he wrote is a popular Paschal canon, including such wonderful prayers as these:

"Let the God-inspired Habakkuk the Prophet stand with us on the holy watch-tower. Let him point out to the radiant Angel who proclaims with vibrant voice: 'Today, Salvation comes to the world, for Christ is risen as All-powerful!'" (Fourth Ode)

"We celebrate the very death of Death and the overthrow of Hell, and the beginning of another life, which is eternal. Let us sing in joy to the Author of these marvels: the only blessed and most glorious God of our Fathers!" (Seventh Ode)

"Shine, shine, O New Jerusalem, for the glory of the Lord has shone upon you. Rejoice and be glad, O Sion, and You, O Pure One, O Mother of God, exult in the Resurrection of Your Son!" (Ninth Ode)

St. John wrote many other popular prayers, used in daily prayers and preparation for receiving the Sacred Mysteries, among other purposes. What may be one of his most popular prayers (as a hint at its popularity, the first line is quoted in Leo Tolstoy's

War and Peace) is a prayer recited just before heading to bed:

"O Lord, Lover of mankind, is this bed to be my coffin, or will You enlighten my wretched soul with another day? Here the coffin lies before me, and here death confronts me. I fear, O Lord, Your Judgment and the endless torments; yet I cease not to do evil. My Lord and God, I continually anger You, and Your Immaculate Mother, and all the Heavenly Powers, and my Holy Guardian Angel. I know, O Lord, that I am unworthy of Your love, but deserve condemnation and every torment. But, whether I want it or not, save me, O Lord. For to save a good man is no great thing, and to have mercy on the pure is nothing wonderful, for they are worthy of Your mercy. But show the wonder of Your mercy to me, a sinner. In this, reveal Your love for man, lest my wickedness prevail over Your unutterable goodness and mercy. And order my life as You will."

To end this post, let us remember with gladness our holy and God-bearing Father, St. John of Damascus, for he defended the holy images, taught us to chant joyful hymns to the Lord in sacred music, expounded the true faith, and gave us many prayers.

"Champion of Orthodoxy, teacher of purity and true worship,

the enlightener of the universe and the adornment of hierarchs:

all-wise father John, your teachings have gleamed with light upon all things.

Intercede before Christ God to save our souls."

(Troparion of the Feast Day of St. John of Damascus, Tone 8)

St. John of Damascus, our holy and God-bearing Father, pray for us!

Nota Bene: Sources of information for this post included OrthodoxWiki (John of Damascus, Cosmas the Hymnographer, Octoechos) and Wikipedia (John of Damascus, Second Council of Nicea). The quote from the Apologies

comes from the translation in On the Divine Images

in the St. Vladimir's Seminary Press' Popular Patristic Series.

Quotes from the Paschal Canon of St. John of Damascus come from the Publican's Prayer Book

by the Melkite Catholic Eparchy of Newton, pp. 297, 302, and 304, respectively; the prayer before bed comes from p. 68 of the same book. The Troparion of St. John's feast day comes from his above-cited OrthodoxWiki article.