In celebration of Trinity Sunday in the Western Church today, I decided to write a short post on the history of artistic representation of the Most Holy Trinity, especially in the East.

Nowadays, there are many representations of the Trinity showing the Three Persons as an old man (the Father), Jesus Christ, and a dove (the Holy Spirit). Before these were in vogue, the Trinity was often depicted symbolically (especially in the Western Church) in forms such as a triangle-encased All-Seeing Eye (a symbol adapted and Christianized from ancient Egyptian symbolism that is, sadly, now usually connected with Freemasonry). In the earliest days of the Church, though, there were no representations of the Trinity apart from the Second Person Incarnate.

Why was this? One main reason was the theological reasoning behind having any images of God in the first place. The Pentateuch declares that we shall have no graven images, so how can there be any religious images, much less images of God Himself? First, "it is not the essence of the image which we venerate, but the form of the prototype which is stamped upon it," as St. Theodore the Studite wrote, thus showing that this is not idolatry (3.C.2). Next, we venerate an image of a body, the body of Christ, for It is truly Him, not a mere body. The body is the person, though the person is not just the body, as Pope Bl. John Paul II's Theology of the Body teaches us. We thus venerate Christ's Body because His Body is Him. As St. John Damascene wrote, "God's Body is God because it is joined to His Person by a union [the hypostatic union] which shall never pass away" (1.16). Though we cannot artistically depict a spirit except symbolically, and though God is spirit, God took on flesh in the Incarnation, thus allowing us to depict Him in the Body of Christ. All this leads to what I consider one of the greatest passages in iconographic theology, brilliantly penned by St. John Damascene:

The last sentence displays the traditional reason for not artistically representing the Trinity: we cannot represent any spirit, much less God. The basic principle of iconography is that we can only make an image of what has become physical: since God became man in Jesus Christ, the Incarnate Word, we can thus make an image of God, but only of the Second Person in His Incarnate Form. Since the First and the Third Persons of the Holy Trinity did not become Incarnate, and thus visible, they cannot be shown in images.

Leonid Ouspensky, an Orthodox scholar, discusses this in his two-volume work Theology of the Icon. The most concise statement is a quote from H.-J. Schulz, which states:

The main problem is that the Trinity is Who God Is, and thus It is at the center of the Christian faith. Thus it seems that the icon, "the book of those who do not know the alphabet," as Pope St. Gregory the Great said, should convey this supreme truth (qtd. in Ouspensky, I:106). It is thus that symbolic representations of the Trinity began.

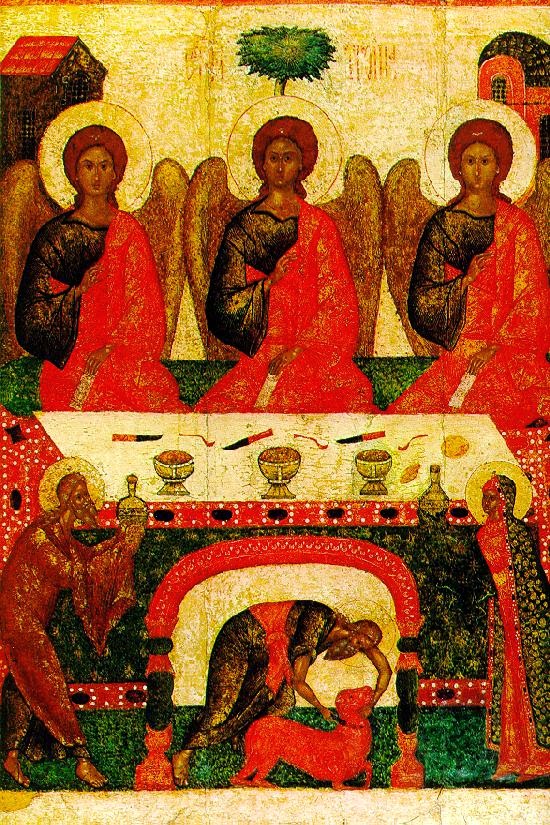

The main artistic representation of the Trinity to appear, at least in the Eastern Church, was the "Old Testament Trinity," exemplified in Andrei Rublev's Троица, which I have discussed before. This icon was based on the story of the three angels visiting Abraham at Mamre, related in Gen 18. Traditional Christian Scripture interpretation has seen these three angels as representing the Three Persons of the Trinity, and, since the angels had some sort of bodily form (they were able to eat, after all), they can thus be represented in an icon to provide a way of representing the Trinity. This is somewhat of a theological stretch, since symbolic representations in icons are often shied away from (for instance, the local Quinisext Council (Council in Trullo) banned representation of Christ as a Lamb, since the Incarnation of Christ supersedes this symbolic representation).

From this, eventually the more current depictions of the Trinity as an old man, Jesus Christ, and a dove came about: since one symbolic representation was already allowed, why not more? This depiction, the "New Testament Trinity," is very common in the Western Church and somewhat less common, though still present, in the Eastern Church, where a more common image is a three-faced men or three identical men (such as can be seen in my post on Ethiopian icons).

(Personally, I am more inclined towards the Old Testament Trinity than the New Testament: I think the depiction seems more theologically accurate, especially of the Father. If we were using true New Testament imagery, the Father should be shown as a cloud (which, I admit, He sometimes is, though not too often, it seems), not a Zeus-like figure. In general, I think the mystery of the lack of imagery of the Father helps us remember that we cannot completely know God.)

In general, the depictions of the Most Holy Trinity grew from no imagery beyond that of the Son to purely symbolic imagery, such as the All-Seeing Eye in a triangle, at least in the Western Church, to representations such as the Old Testament Trinity to the modern image of an old man, Jesus Christ, and a dove. Through all my digressions, quotes, and personal opinions, that is the point of this post.

Finally, since in the Eastern Church today is All Saints Sunday, I will end with a quote from St. John Damascene defending iconography of the saints against an iconoclastic emperor:

Thank you for reading, and God Bless.

Most Holy Trinity, have mercy on us!

Nota Bene: The quote from St. Theodore the Studite comes from his Refutation of the Iconoclasts, and the quotes from St. John Damascene come from his Apology Against Those Who Attack the Divine Images; all quotes come from the versions of these works published in St. Vladimir Seminary Press' Popular Patristics Series. The quotes from Leonid Ouspensky come from his Theology of the Icon, published by St. Vladimir's Seminary Press in 1992.

Nowadays, there are many representations of the Trinity showing the Three Persons as an old man (the Father), Jesus Christ, and a dove (the Holy Spirit). Before these were in vogue, the Trinity was often depicted symbolically (especially in the Western Church) in forms such as a triangle-encased All-Seeing Eye (a symbol adapted and Christianized from ancient Egyptian symbolism that is, sadly, now usually connected with Freemasonry). In the earliest days of the Church, though, there were no representations of the Trinity apart from the Second Person Incarnate.

Eye of God, Mission San Miguel, California (19th century)

Why was this? One main reason was the theological reasoning behind having any images of God in the first place. The Pentateuch declares that we shall have no graven images, so how can there be any religious images, much less images of God Himself? First, "it is not the essence of the image which we venerate, but the form of the prototype which is stamped upon it," as St. Theodore the Studite wrote, thus showing that this is not idolatry (3.C.2). Next, we venerate an image of a body, the body of Christ, for It is truly Him, not a mere body. The body is the person, though the person is not just the body, as Pope Bl. John Paul II's Theology of the Body teaches us. We thus venerate Christ's Body because His Body is Him. As St. John Damascene wrote, "God's Body is God because it is joined to His Person by a union [the hypostatic union] which shall never pass away" (1.16). Though we cannot artistically depict a spirit except symbolically, and though God is spirit, God took on flesh in the Incarnation, thus allowing us to depict Him in the Body of Christ. All this leads to what I consider one of the greatest passages in iconographic theology, brilliantly penned by St. John Damascene:

"Therefore I boldly draw an image of the invisible God, not as invisible, but as having become visible for our sakes by partaking of flesh and blood. I do not draw an image of the immortal Godhead, but I paint the image of God Who became visible in the flesh, for if it is impossible to make a representation of a spirit, how much more impossible is it to depict the God Who gives life to the spirit?" (1.4).

Pantokrator icon, St. Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai (7th century)

The last sentence displays the traditional reason for not artistically representing the Trinity: we cannot represent any spirit, much less God. The basic principle of iconography is that we can only make an image of what has become physical: since God became man in Jesus Christ, the Incarnate Word, we can thus make an image of God, but only of the Second Person in His Incarnate Form. Since the First and the Third Persons of the Holy Trinity did not become Incarnate, and thus visible, they cannot be shown in images.

Leonid Ouspensky, an Orthodox scholar, discusses this in his two-volume work Theology of the Icon. The most concise statement is a quote from H.-J. Schulz, which states:

"A visible representation of what is essentially invisible is, for this theology of the icon, not merely ostentatious or foolish. It is heresy or sacrilege, because it is an arbitrary addition to revelation and to the divine economy and, in this present case, also a heresy asserting an incarnation of the Father and of the Holy Spirit" (II:395).

The main problem is that the Trinity is Who God Is, and thus It is at the center of the Christian faith. Thus it seems that the icon, "the book of those who do not know the alphabet," as Pope St. Gregory the Great said, should convey this supreme truth (qtd. in Ouspensky, I:106). It is thus that symbolic representations of the Trinity began.

The main artistic representation of the Trinity to appear, at least in the Eastern Church, was the "Old Testament Trinity," exemplified in Andrei Rublev's Троица, which I have discussed before. This icon was based on the story of the three angels visiting Abraham at Mamre, related in Gen 18. Traditional Christian Scripture interpretation has seen these three angels as representing the Three Persons of the Trinity, and, since the angels had some sort of bodily form (they were able to eat, after all), they can thus be represented in an icon to provide a way of representing the Trinity. This is somewhat of a theological stretch, since symbolic representations in icons are often shied away from (for instance, the local Quinisext Council (Council in Trullo) banned representation of Christ as a Lamb, since the Incarnation of Christ supersedes this symbolic representation).

Trinity, Andrei Rublev (1410)

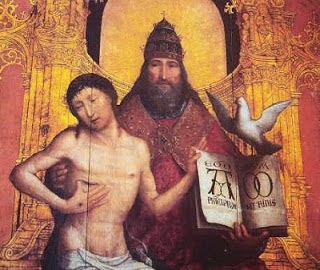

From this, eventually the more current depictions of the Trinity as an old man, Jesus Christ, and a dove came about: since one symbolic representation was already allowed, why not more? This depiction, the "New Testament Trinity," is very common in the Western Church and somewhat less common, though still present, in the Eastern Church, where a more common image is a three-faced men or three identical men (such as can be seen in my post on Ethiopian icons).

(Personally, I am more inclined towards the Old Testament Trinity than the New Testament: I think the depiction seems more theologically accurate, especially of the Father. If we were using true New Testament imagery, the Father should be shown as a cloud (which, I admit, He sometimes is, though not too often, it seems), not a Zeus-like figure. In general, I think the mystery of the lack of imagery of the Father helps us remember that we cannot completely know God.)

Detail from Triptych of the Trinity by Jean Bellegambe (1513-1518)

In general, the depictions of the Most Holy Trinity grew from no imagery beyond that of the Son to purely symbolic imagery, such as the All-Seeing Eye in a triangle, at least in the Western Church, to representations such as the Old Testament Trinity to the modern image of an old man, Jesus Christ, and a dove. Through all my digressions, quotes, and personal opinions, that is the point of this post.

Finally, since in the Eastern Church today is All Saints Sunday, I will end with a quote from St. John Damascene defending iconography of the saints against an iconoclastic emperor:

"We depict Christ as our King and Lord, then, and do not strip Him of His army. For the saints are the Lord's army. If the earthly emperor wishes to deprive the Lord of His army, let him also dismiss his own troops. If he wishes in his tyranny to refuse due honor to these valiant conquerors of evil, let him also cast aside his own purple." (1.21).

Thank you for reading, and God Bless.

Most Holy Trinity, have mercy on us!

Holy Trinity, Pskov School (15th century)

Nota Bene: The quote from St. Theodore the Studite comes from his Refutation of the Iconoclasts, and the quotes from St. John Damascene come from his Apology Against Those Who Attack the Divine Images; all quotes come from the versions of these works published in St. Vladimir Seminary Press' Popular Patristics Series. The quotes from Leonid Ouspensky come from his Theology of the Icon, published by St. Vladimir's Seminary Press in 1992.

Text ©2012 Brandon P. Otto. Licensed via CC BY-NC. Feel free to redistribute non-commercially, as long as credit is given to the author.

No comments:

Post a Comment